Finance – Bonds

One of the big things in the financial world are bonds. They are like James Bond except, well, they aren’t a cool spy. I would say that they are boring, but that would be a lie. At first, they seem boring, but then become fascinating over time. It’s like watching Dr. No. The first time the movie is fine, but then it gets better each time you watch it. Bonds are like that you know.

So, here is a quick 10-step rundown on bonds.

- Bonds are dressed-up debt payments (like your car loan)

Governments and companies issue bonds to provide them with funds for their operations or specific projects. When you purchase a bond, you are essentially loaning your cash for a certain period of time to the issuer (whether it be Apple, Google, or Uncle Sam). They get your cash and use it for their projects. What you get is that money returned plus interest payments.

- Bonds are misunderstood investments and can provide a better return than stocks

It is only in the post-World War II age that stocks so widely outpaced bonds in the total-return derby. Stock and bond returns were about even from about 1880 to 1940. And, of course, bonds were well in front in 2000, 2001 and 2002 prior to stocks once again took charge in 2003 and 2004. By 2008, nevertheless, the bond market had far outpaced the stock exchange once again, and did so once again in 2011. Given the large run-up in stock prices, it should not be a surprise to see bonds once again take the lead.

- But bonds aren’t totally safe, either

Bonds are not turbo-charged CDs. Though their life expectancy and interest payments are dealt with– hence the term “fixed-income” financial investments– their returns are not. You can lose money in the bond market.

- The bond price will move in the opposite direction of interest rates

This can be hard to fully comprehend. When interest rates fall, the price of the bond will rise (and vice versa).

So, let’s walk through a very quick example. Let’s say that a bond will pay 10% per year in interest and has a term of one year. So, if you buy the bond on day 1, it will cost $90 for a $100 payoff in a year (10% of $100 is $10). So, the company gets $91 for a year and you get $100 a year from now.

But let’s assume that the interest rate market goes way down. Thus, on day 2, the interest rate goes down to 5%. The bond is now worth $95 (as you only get 5% interest from then on). Thus, the bond price goes UP when the interest rate goes DOWN.

- Bond mutual funds are not the same as a single bond

With a bond, you always get your interest and principal at maturation, assuming the issuer doesn’t go belly up. With a mutual fund, your return is uncertain since the fund’s value changes. The mutual fund is based on a composite of the different bonds within it.

- Bonds are great, but they aren’t everything

Inflation erodes the value of bonds’ fixed interest payments. Stock returns, by contrast, stand a better chance of outpacing inflation over time. Despite the drubbing stocks often take, middle-aged and young individuals are advised to put some piece of their cash in stocks. What’s more, the current models suggest that senior citizens need to have some stocks, given that people are living longer.

- Don’t forget about tax-free bonds

Municipal bonds get a bad rap. But don’t forget about tax-exempt bonds. More importantly, take into account the tax break when figuring your total return. These bonds can still be the much better choice for taxable accounts.

- It’s all about the total return, not just the stated yield

Returns are a slippery matter in the bond world. A broker could offer you a bond that is paying a “coupon” – or interest rate – of 6 %. If interest rates rise, however, and the rate of the bond falls by, say, 2 %, its overall return for the very first year – 6 % in income less a 2 % capital loss – would be only 4 %.

- Capital gains matter

You should keep bonds for a long term time to get them to appreciate and get you capital gain treatment on the bond appreciation. However, this is more akin to stock picking – just in the bond market. Take care as this is speculative and could also lead to large losses.

- Investors trying to find income ought to buy a laddered portfolio of brief- and intermediate-term bonds.

About Bonds

Bonds can provide a worry-free stream of earnings. However this course of securities, which crushed stocks during the three-year bearishness of 2000 through 2002, likewise includes a large range of instruments with varying degrees of risk and benefit.

Used poorly, bonds can truly mess up your financial life. Handled with care, however, bonds are among the most important tools in your financial investment kit. Here are some of the benefits they can supply:

– Security. Alongside cash, U.S. Treasuries are the best, most liquid investments on the planet. Short-term bonds are a good location to park an emergency fund or money you’ll need fairly soon – say to purchase a home or send a child to college.

– Diversification. Big business stocks have posted compound annual returns of almost 10 % considering that 1926, versus 5.7 % for long-term U.S. government bonds, according to Ibbotson Associates. While stocks have actually returned more than bonds, they are likewise more unstable. Incorporating stocks with bonds will certainly net you a steadier portfolio. As seen throughout the bearish market, bonds’ favorable returns balance out the double-digit losses from stocks.

– Tax savings. Certain bonds offer tax-free income. Although these bonds normally pay lower yields than equivalent taxable bonds, investors in high tax brackets (generally, 28 % and above) can commonly earn greater after-tax returns from tax-free bonds.

– Income. They are a good choice for investors– such as retired people– who want a stable stream of income because bonds pay interest routinely.

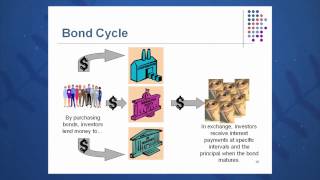

Business and governments issue bonds to fund their daily operations or to finance particular jobs. When you purchase a bond, you are loaning your money for a certain time period to the issuer, be it General Electric or Uncle Sam.

In exchange, the borrower promises to pay you interest every year and to return your principal at “maturity,” when the loan comes due, or at “call” if the bond is of the type that can be called earlier than its maturity (more on this later). The length of time to maturation is called the “term.”

A bond’s face value, or rate at issue, is referred to as its “par value.” Its interest payment is referred to as its “discount coupon.”

A $1,000 bond paying 7 % a year has a $70 discount coupon (really, the money would generally show up in two $35 payments spaced six months apart). Revealed another method, its “voucher rate” is 7 %. If you purchase the bond for $1,000 and hold it to maturity, the “yield,” or actual profits on your investment, is likewise 7 % (voucher rate divided by price = yield).

The prices of bonds fluctuate throughout the trading day as, of course, do their yields. But the voucher payments remain the exact same.

State you don’t buy the bond right at the providing, and rather buy from somebody else in the “secondary” market. If you purchase the bond for $1,100 in the secondary market, though, the discount coupon will certainly still be $70, however the yield is 6.4 % since you paid a “premium” for the bond.

For a comparable factor, if you buy it for $900, its yield will be 7.8 % due to the fact that you bought the bond at a “price cut.” If its present price equals its stated value, the bond is stated to be selling at “par.”

The bottom line: There are many ways of revealing a bond’s return, however “total return” is the only one that really matters. This consists of all the money you make off the bond: the yearly interest and the gain or loss in market value, if any.

If you sell that $1,000 bond with the $70 coupon for $1,050 after one year, your overall return is $120, or 12 %– $70 in interest and $50 in capital gains. (Costs are generally revealed based on a par value of 100, so when you offer that bond for $1,050 the price would be priced quote as 105.).

U.S. Treasuries are the safest bonds of all because the interest and principal payments are guaranteed by the “full faith and credit” of the united state government. Interest is exempt from state and local taxes, but not from federal tax. Treasuries carry some of the least expensive yields around because of their virtually overall lack of default risk.

Treasury bonds come in a variety of forms

– Treasury expenses, or “T-bills,” have the shortest maturities – 13 weeks, 26 weeks, and one year. You purchase them at a discount rate to their $10,000 face value and get the complete $10,000 at maturity. The distinction shows the interest you make.

– Treasury notes mature in 2 to 10 years. Interest is paid semiannually at a fixed rate. Minimum financial investment: $1,000 or $5,000, depending upon maturation.

– Treasury bonds have the longest maturations at 10 years. Similar to Treasury notes, they pay interest semiannually, and are offered in denominations of $1,000.

– Zero-coupon bonds likewise referred to as “strips” or “zeros,” are Treasury-based securities that are sold by brokers at a deep price cut and redeemed at full face value when they develop in 6 months to 30 years. Although you don’t really get your interest until the bond matures, you must pay taxes each year on the “phantom interest” that you make (it’s based upon the bond’s market price, which normally rises steadily during the time you hold it). Because of that, they are best held in tax-deferred accounts. Just remember that the price can be highly volatile as there is not a coupon being paid

You do not collect the inflation modification to your principal till the bond matures or you sell it, but you owe federal earnings tax on that phantom quantity each year – in addition to tax on the interest you receive currently. Like zero coupon bonds, inflation bonds are best held in tax-deferred accounts.

– Mortgage-backed securities stand for an ownership stake in a bundle of mortgage issued or guaranteed by government firms such as the Government National Home mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae), Federal Home mortgage Home mortgage Corp. (Freddie Mac), and Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae). Interest is taxable and is paid monthly, along with a partial repayment of principal. Ginnie Mae has actually always been backed by the complete faith and credit of the U.S. government. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, on the other hand, have been under government control since Sept. 2008, putting Uncle Sam on the hook to guarantee their mortgage-backed securities. The financial meltdown of 2007 showed that bonds can have some risk with them. Bonds that are backed by a mortgage have greater returns than Treasuries of similar maturities (around 2-4% more). Minimum investment: generally $25,000.

– Corporate bonds pay taxable interest. The majority of are released in denominations of $1,000 and have regards to one to 20 years, though maturities can vary from a few weeks to 100 years. Because their value depends on the creditworthiness of the company offering them, corporates bring higher risks and, for that reason, greater yields than super-safe Treasuries. High-quality corporates are referred to as “investment-grade” bonds. Corporates with lower credit quality are called “high-yield,” or “junk,” bonds. Junk bonds usually pay greater yields than other corporates.

– Municipal bonds, or “munis,” are one of America’s favorite tax shelters. They are issued by state and local governments and firms, typically in denominations of $5,000 and up, and mature in one to 30 or 40 years. Interest is exempt from federal taxes and, if you live in the state providing the bond, state and potentially local taxes. (Note that there are exceptions). The capital gain you could make if you sell a bond for more than it cost you to buy it is just as taxable as any other gain; the tax-exemption applies only to your bond’s interest.

Municipal bonds generally offer lower yields than taxable bonds of comparable duration and quality. Because of their tax advantages, though, their after-tax returns are typically higher than equivalent taxable bonds for individuals in the 28 % federal tax bracket or above.

Lots of people think they can’t lose money in bonds. Wrong! The interest payments you’ll get from owning a bond are “fixed,” your return is anything.

What are the Risks that can deteriorate the return on your bond?

Inflation threat.

Given that bond interest payments are fixed, their value can be deteriorated by inflation. The longer the time to maturation of the bond, the greater the inflation risk. Bonds have traditionally been a hedge against deflation.

Interest rate threat.

Bond rates relocate the opposite direction of rate of interest. When rates rise, bond costs fall because new bonds are released that pay higher vouchers. This makes old bonds, especially those with lower yields less attractive to investors. On the other hand, bond prices increase when interest rates go down.

The longer the regard to the bond, the greater the cost change – or volatility – that results from any modification in rate of interest.

There is a close connection in between inflation threat and rate of interest danger considering that rate of interest have the tendency to rise together with inflation. Interest rate shifts are likewise an issue for mortgage-backed bondholders, but for a different reason: If rate of interest fall, home owners could choose to prepay their current mortgages and obtain new ones at the lower rates.

That does not suggest you’ll lose your principal if you hold such a bond. But it does mean you get your principal back much sooner than expected, compelling you to reinvest it at the newly lower rates. For that reason, the costs of mortgage-backed securities don’t get as big a boost from falling rates as other sort of bonds.

Keep in mind that rate fluctuations only matter if you mean to offer a bond prior to maturity, or you invest in a bond fund whose manager trades regularly. If you hold a bond to its maturity, you will be paid back the bond’s complete face value.

However what if rate of interest fall and the issuer of your bond wishes to decrease its interest expenses? This brings us to the next kind of threat…

Call risk.

Many corporate and muni bond issuers reserve the right to redeem, or “call,” their bonds before they develop, at which point the issuer is needed to pay bondholders only par value. Generally, this happens if rate of interest fall and the issuer sees it can reduce its expenses by selling brand-new bonds with lower yields.

If you occur to have one of the called bonds, not just do you get less than the marketplace cost of the bond, but you also have to find a place to reinvest the cash. Because of the danger that you won’t get the earnings you expect, callable bonds usually pay a higher rate of interest than similar, non-callable bonds. When you buy bonds, make sure to ask not just about the time to maturity, however likewise about the time to a most likely call.

Credit risk.

This is the danger that your bond issuer will be not able to make its payments on time – or at all – and it depends on the kind of bond you own and the borrower’s financial health. U.S. Treasuries are thought about to have essentially no credit risk, junk bonds the greatest.

Scrap bonds are rated Ba and lower from Moody’s, or BB and lower from S&P. (You can inspect out a bond’s rating for complimentary by calling S&P at 212-438-2400 or Moody’s at 212-553-0377, or by examining some of the bond websites we recognize in “Buying bonds.”).

The highest-quality community bonds are backed by bond insurance provider companies, however there is a trade-off: Insured municipal bonds generally yield as much as 0.3 % points less than equivalent uninsured municipal bonds. Additionally, the insurance just guarantees your interest and principal; it will not protect you versus interest rate or market danger.

Some higher-coupon munis are likewise “pre-refunded,” meaning that, for esoteric reasons, they are successfully backed by U.S. Treasuries. When a muni is pre-refunded by an issuer, its credit quality and rate increase.

Liquidity danger.

In general, bonds aren’t almost as liquid as stocks since investors have the tendency to buy and hold bonds rather than trade them. While there is constantly a ready market for super-safe Treasuries, the markets for other bonds, particularly municipal bonds and junk bonds, can be highly illiquid. If you are required to discharge a thinly-traded bond, you will most likely get a low price.

Market risk.

Just like most other investments, bonds follow the laws of supply and need. The more popular or less plentiful a bond, the higher the price it commands in the market. Throughout economic crises in Asia and Russia, for example, the rate of safe-haven U.S. Treasuries rose considerably.

You cannot get rid of these risks completely. Now that you comprehend them, you could be able to decrease their effect by some of the techniques described in the next section of this lesson.

Here are some of the primary methods ways that you can buy a bond:

Straight from the Feds.

U.S. Treasuries are sold by the federal government at routinely scheduled auctions. You can purchase them with a bank or broker for a cost, but why spend for something you can get for nothing? The most convenient and least expensive way to take part in this market is to buy them straight from the Treasury. You can check out the Treasury Direct program or by calling 800-722-2678.

With a broker.

With the exception of Treasuries, purchasing individual bonds isn’t for the faint of heart. Most brand-new bonds are provided through a financial investment bank, or “underwriter,” rather than directly to the general public. The issuer ingests the sales commission, so you get the same cost big investors pay.

That’s why, when buying individual bonds, you must purchase new issues straight from the underwriter whenever possible – because you’re getting them at wholesale. Sometimes, you need to be sure that you find a great bond company. See Swiftbonds.com for more information.

Older bonds are another matter. They are traded with brokers on the “secondary market,” typically over the counter instead of on an exchange, such as the New York Stock Exchange. Right here, transaction costs can be much higher than with stocks because spreads – the difference in between exactly what a dealership spent for a bond and exactly what he’ll sell it for – tend to be wider.

You will rarely know what spread you paid, regrettably, since the markup is set by the dealer and constructed into the price of the bond. There is no set commission schedule. One ray of sunshine: In early 2002 the Bond Market Association began publishing some muni bond costs on its internet site. Alas, the rates consist of dealership markups due to the fact that dealerships objected providing commissions separately.

If you do plan to purchase individual bonds, you need to probably have enough money to invest – state $25,000 to $50,000 at a minimum – to accomplish some degree of diversification. Consider bond funds if you have less.

Precisely how you invest depends largely on your goal

Reason: as noted in “Sizing up threats,” the longer the term of a bond, the more pronounced are its cost swings when interest rates move. Your long-lasting bonds – specifically zero-coupon bonds – will unexpectedly be worth a lot more. This kind of bond investing is basically a bet that interest rates will fall, and it’s subject to all the same risks – including that of substantial losses – as any other market-timing technique.

– If your objective is a stable, secure stream of earnings, embrace a more conservative strategy.

Stick to much shorter terms. Bonds with maturations of one to 10 years suffice for many long-lasting investors. They yield more than shorter-term bonds, and are less unstable than longer-term concerns.

Spread your money around. Buy a variety of bonds with various maturities, either by buying a bond fund or buying a half-dozen or more individual bonds.

Each rung of your ladder consists of a different maturity bond, from one year right on up to 10 years. When the one-year bond develops, you reinvest the cash in a brand-new, 10-year concern.

With a mutual fund.

It can make good sense to buy individual bonds if you possess a great deal of them and hold them to maturation, however most people are better off purchasing bonds through mutual funds. The greatest factor is diversification. Due to the fact that bonds are offered in large units, you might only have the ability to acquire one or a handful of bonds on your own, however as a bond fund holder you’ll own stakes in dozens, perhaps hundreds, of bonds.

You will certainly likewise get the benefit of expert research and finance. Another benefit: Dividends are paid monthly, versus just semiannually for individual bonds, and can be reinvested immediately. Bond funds are more liquid than individual bond concerns.

The greatest downside to bond funds – and it’s a whopper – is that they do not have a dealt with maturation, so that neither your principal nor your income is guaranteed. Fund managers are continuously buying and selling bonds in their portfolios to maximize their interest income and capital gains. That implies your interest payments will certainly differ, as will certainly the fund’s share rate.

For this reason, don’t choose a fund based just on its yield. Take a look at its total return, which integrates the earnings the fund paid out with any change in the value of the fund’s shares. Look for a fund with low expenses.

Due to the fact that mutual fund with similar financial investment objectives have the tendency to hold comparable types of securities, which carry out likewise, there are just two ways a fund manager can goose the yield: cut costs or handle more risk. If a fund’s yield is more than 1 percentage point higher than the average for its peers and the difference can’t be discussed by lower fees, the manager is most likely meddling exotic bond derivatives.